Page Nethercutt uses tweezers to carefully adjust a newly mounted water duck skin. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

Page Nethercutt sits at a table, glasses on his nose, needle and thread in hand. On the table are four orange and black acrylic half-circles, a few brushes and two bird skins. One sits to the side, the other is being sewn shut around a molded, lightweight foam bird body.

Nethercutt is sewing up the skin around a form that looks several sizes too small, but there’s a reason for that. “With a bird, you have to have your body small so that the feather quills don't bind against it as it dries, or else it'll distort the look of your bird,” Nethercutt explains.

On the day we meet, he’s working on two sea ducks, formerly known as oldsquaw and now called long-tailed ducks. They’ll be mounted standing, looking out at the observer.

They’re two of nearly a hundred or so birds Nethercutt is working on as part of a decadeslong taxidermy tradition he learned from his father and demonstrated as an expert on the 2013 AMC reality TV series “Immortalized.”

Moore’s Swamp Taxidermy, named after the road it’s on, has a New Bern address, though it is located within Pamlico County. Some of his many pieces are in progress around his workspace there.

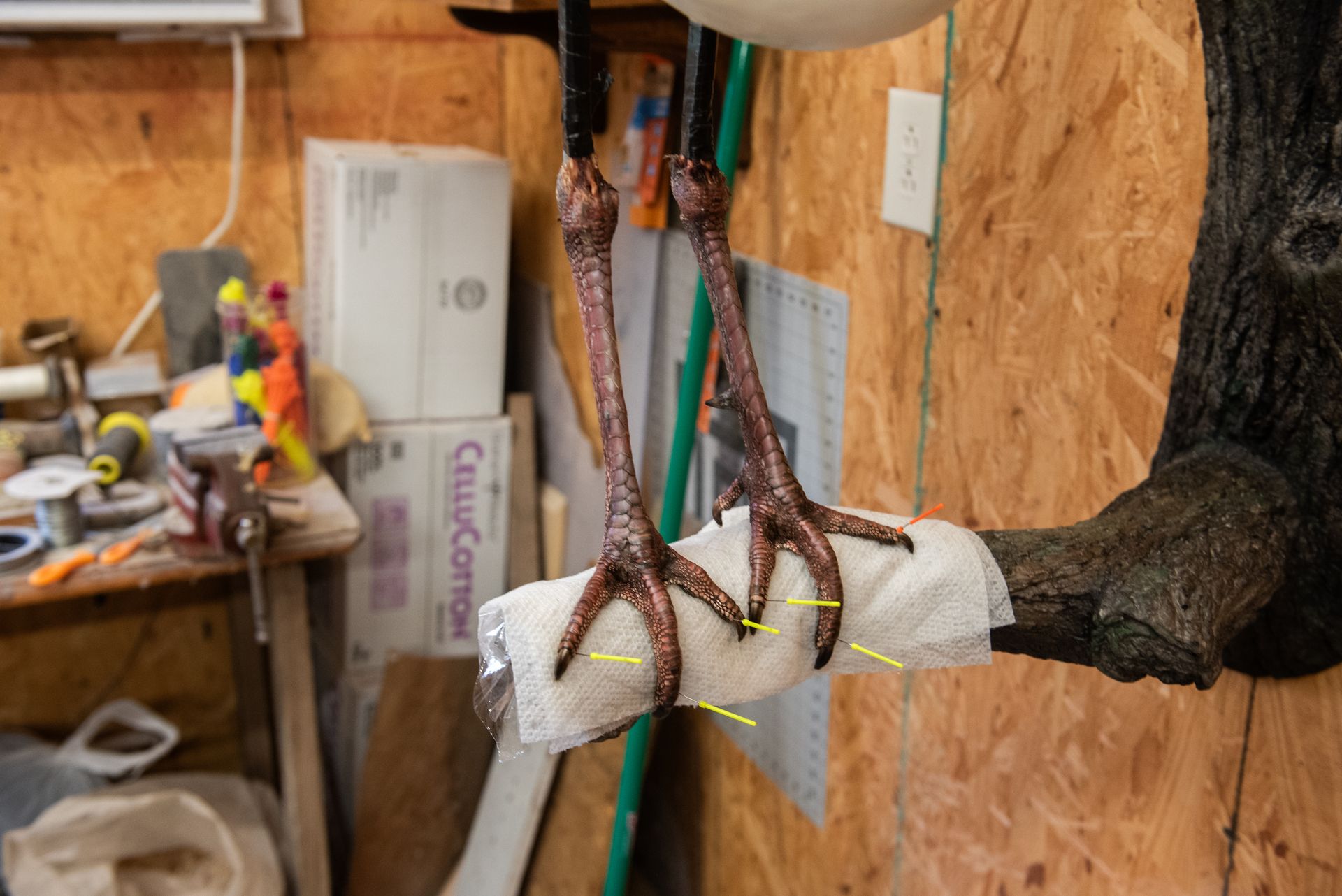

Near his worktable are the feet and tail feathers of two turkeys, both assembled on molded foam bodies and mounted on stands. The skins and heads will go on after the feet are dry and painted. Several turkey heads — not from the same turkeys — wait across the room for their bodies to be finished.

Several mounted birds hang from a wall, each at a different phase in the dayslong drying process.

Nethercutt, now in his early 50s, says he does two birds a day, start to finish. That includes skinning, washing, cleaning, drying, preserving and mounting.

When he was younger, he said, he could complete up to three a day.

The work on display is exceptional. Prize ribbons are draped on some of the pieces while a wall and an entryway desk display close to 100 plaques, certificates and commendations from competitions worldwide. Among these is a plaque from the North Carolina Taxidermist’s Association declaring Nethercutt a Master Taxidermist. He is one of only 20 people in the state to hold the designation.

Nethercutt grabs a molded bird skull — one of his own creations — and applies epoxy to hold in the acrylic eyes and build out the features around the socket. Once the eyes are in place, the molded head will slide onto a cotton-wrapped armature, or framework, and Nethercutt will pull the skin up around it.

As he fits the skin into place around the drying epoxy, Nethercutt explains that the centuries-old art form isn’t just about taking an animal apart and putting it back together.

Tools of the trade: a blush brush and pair of tweezers are as important as the acrylic eyes and a painted sculpted skull.(Photo by Allison DeWeese)

Fitting the skin around a molded skull is precision work. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

Mounted, but not finished. Nethercutt will spend a good 45 minutes adjusting the fit of the skin and carefully guide the feathers into place. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

Nethercutt’s work and award ribbons on display in the entrance of Moore’s Swamp Taxidermy. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

“A taxidermist has got to be a seamstress, a carpenter, a butcher, a mason, a painter — everything,” he says. “It's a lot more demanding than what people think.”

Part of that skill set is creating the bird skull molds Nethercutt uses in his taxidermy. He wasn’t intending on adding that to his business, but the Texas winter storms of 2021 and the pandemic changed a lot of the business, for Nethercutt specifically and the taxidermy world in general.

Prior to 2021, Nethercutt also mounted big game: deer, elk, moose, giraffes, buffalo, bears. “For 10 years, I collected clients from all over the country, and we’ve mounted, I don’t know, about 65 to 70% of all the big game you can hunt,” he says.

One of the larger companies that provided foam for the mammal forms was located in Texas. And they froze.

“You’d put in an order for materials and it would take four to five months to get it in when it used to take two days,” he says. “And the boy that made most of the eyes — the eyes were made of glass — his wife got extremely ill, and he closed his business to take care of his wife.” Nethercutt had to find a new supplier in Europe.

This, combined with fewer overhead costs for birds, pushed Nethercutt to focus solely on birds and start manufacturing his own skull molds. “There’s about eight of us that supply all the bird products for everyone in the country,” he says.

Nethercutt has worked in the industry for a long time; his father, Gerald, was a taxidermist and would pay him to skin out animals. Gerald Nethercutt had his own taxidermy shop from 1963 until he retired in 1987.

During that time, Page Nethercutt went into the military after high school. “After my military term was up, I came home and decided this is what I wanted to do,” he says. “And so in September of 1994, I reopened his old shop under a new name.”

Painted turkey heads waiting for their body mounts. They’ve been waiting a while. These are for his personal collection, but the work for clients comes first. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

Turkey feet placed on the mount. Once dry, Nethercutt will apply paint to maintain a vibrant life-like look. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

It was originally his father’s old shop, but he called it Moore’s Swamp Taxidermy. It became his full-time job. Nethercutt has since moved to a workspace down the road as flooding from Goose Creek rendered the old shop unusable.

In the 31 years since, Nethercutt has won multiple awards for his taxidermy and is a guest teacher and judge at several taxidermy shows around the country.

On the AMC show “Immortalized,” he served as one of four “immortalizers,” professionals who faced off against amateur taxidermy challengers on each episode.

Last month, Nethercutt and his wife, Bonnie, traveled to New Zealand, where he served as an international judge at the New Zealand Taxidermy Association’s 2025 Competition.

As we talk, he finishes the mount using tweezers to carefully arrange the wing feathers of the bird into two points. He explains as he goes.

“Well, people want to do this,” he says while pushing apart the feathers he’s arranging. “Split 'em open like this. Now this is what a pintail does. Not an oldsquaw. An oldsquaw keeps theirs together. And they basically only show two points, like so.

“So besides understanding basic feather groups, you also have to have some interspecies knowledge so that you can see things in particular that each species likes to do,” he says.

This is part of Nethercutt’s artistry. He pays close attention, knows what each bird is supposed to look like. In flight. On the ground. In the water. His background as a hunter helps, but so do his studies. “When you understand how a bird flies, then it’s easier to mimic the reference pictures,” he says.

He explains how the flaps on a plane’s wing mimic the alula, or thumb, on a bird’s wing, with both helping maintain equal air pressure between the top and bottom of the wing. Nethercutt points to a wood duck drying on the wall. It’s turned on its side, wings lifted.

“If he turns his wing more perpendicular to the ground, he loses that airflow and he'll fall,” Nethercutt says. “That's where the thumb pops up and it grabs air and forces it down over these feathers right here and helps maintain his lift so he doesn't fall out of the air. You typically see it in mostly landing poses and some jumping poses.”

Female wood duck posed in flight. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

Page Nethercutt at work on an oldsquaw. Another waits nearby. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

It’s a dynamic pose, and one that his customers often request.

Nethercutt brings that same artistic eye and knowledge when he judges, though he’s on the fence about some of the judging criteria these days. “They want everything to be perfectly symmetrical when there is no symmetry in nature,” he says. “All you gotta do is look in the mirror.”

Nethercutt describes himself as more of a realist in this regard. “Let's say that bird ended up being hot pink when he shot it,” Nethercutt says. “And he mounted it and it's hot pink. Well, that's what the bird is. I'm not going to dock you for it.”

All that being said, if you bring in your birds to Moore’s Swamp, Nethercutt will help you choose the best one for display.

He knows his price is on the higher end; ducks start at $520. A turkey can run up to $1,950, depending on the mount. And should you bring in an ostrich, expect a cost up to $6,500. You’ll get what you pay for: a show-worthy piece by a master craftsman.

Just don’t bring in any mammals or pets. The only mammals he takes on these days are those he and his wife hunt.

He won’t work on pets, he says, because they are capable of showing emotion in ways wild animals can’t. “If some lady’s had her dog for 15 years, there’s a look in that dog’s face that I cannot reproduce,” he says. “She would always be upset with it.”

If you’d like to have your birds prepared by one of the best, Page Nethercutt is taking clients. But be prepared to wait. There are two freezers full of birds to get through and the current wait time is 18 months.

In the meantime, you can see his work on the Moore’s Swamp Taxidermy Facebook page or watch him on “Immortalized.”

Nethercutt adjusts the feet of the mount before placing it on the display. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

The road to Moore’s Swamp Taxidermy. (Photo by Allison DeWeese)

Donate and become a vital part of growing a visual and written history of the county.

Down in the County has its own Instagram page! Check us out @downinthecounty